Lessons In Samādhi

MAIN CONTENT

Lessons in Samādhi

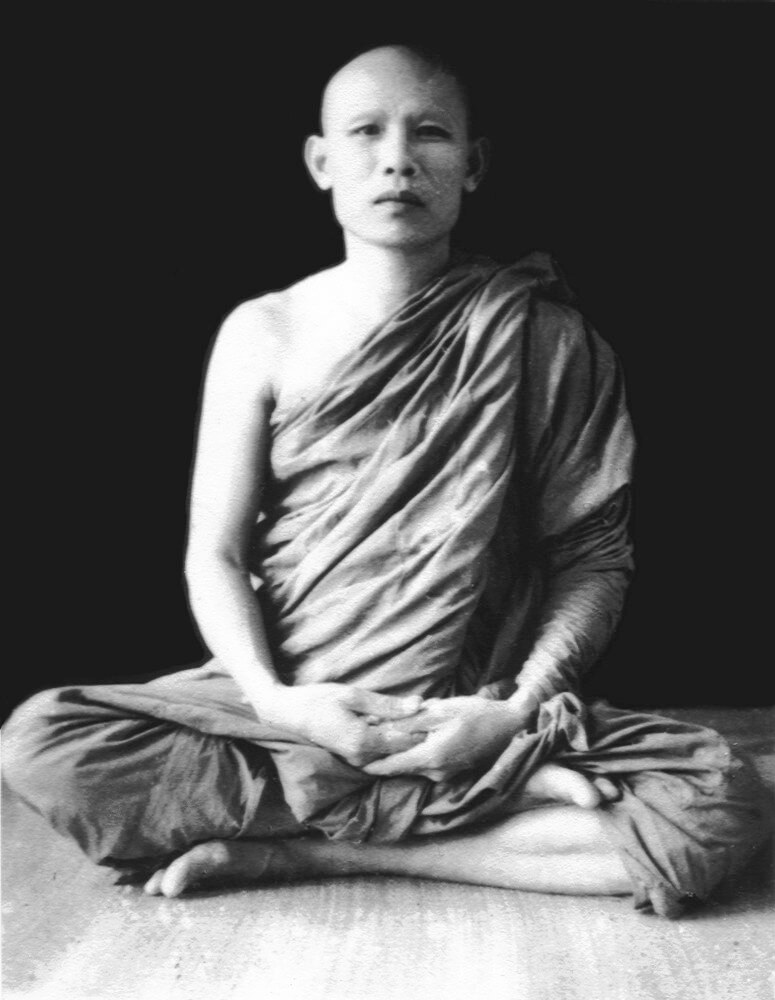

Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo

Groundwork

July 30, 1956

IF, WHEN YOU’RE SITTING, you aren’t yet able to observe the breath, tell yourself, ‘Now I’m going to breathe in. Now I’m going to breathe out.’ In other words, at this stage you’re the one doing the breathing. You’re not letting the breath come in and out as it naturally would. If you can keep this in mind each time you breathe, you’ll soon be able to catch hold of the breath.

In keeping your awareness inside your body, don’t try to imprison it there. In other words, don’t try to force the mind into a trance, don’t try to force the breath or hold it to the point where you feel uncomfortable or confined. You have to let the mind have its freedom. Simply keep watch over it to make sure that it stays separate from its thoughts. If you try to force the breath and pin the mind down, your body is going to feel restricted and you won’t feel at ease in your work. You’ll start hurting here and aching there, and your legs may fall asleep. So just let the mind be its natural self, keeping watch to make sure that it doesn’t slip out after external thoughts.

When we keep the mind from slipping out after its concepts, and concepts from slipping into the mind, it’s like closing our windows and doors to keep dogs, cats, and thieves from slipping into our house. What this means is that we close off our sense doors and don’t pay any attention to the sights that come in by way of the eyes, the sounds that come in by way of the ears, the smells that come in by way of the nose, the tastes that come in by way of the tongue, the tactile sensations that come in by way of the body, and the preoccupations that come in by way of the mind. We have to cut off all the perceptions and concepts—good or bad, old or new—that come in by way of these doors.

Cutting off concepts like this doesn’t mean that we stop thinking. It simply means that we bring our thinking inside to put it to good use by observing and evaluating the theme of our meditation. If we put our mind to work in this way, we won’t be doing any harm to ourself or to our mind. Actually, our mind tends to be working all the time, but the work it gets involved in is usually a lot of nonsense, a lot of fuss and bother without any real substance. So we have to find work of real value for it to do—something that won’t harm it, something really worth doing. This is why we’re doing breath meditation, focusing on our breathing, focusing on our mind. Put aside all your other work and be intent on doing just this and nothing else. This is the sort of attitude you need when you meditate.

The hindrances that come from our concepts of past and future are like weeds growing in our field. They steal all the nutrients from the soil so that our crops won’t have anything to feed on and they make the place look like a mess. They’re of no use at all except as food for the cows and other animals that come wandering through. If you let your field get filled with weeds this way, your crops won’t be able to grow. In the same way, if you don’t clear your mind of its preoccupation with concepts, you won’t be able to make your heart pure. Concepts are food only for the ignorant people who think they’re delicious, but sages don’t eat them at all.

The five hindrances—sensual desire, ill will, torpor & lethargy, restlessness & anxiety, and uncertainty—are like different kinds of weeds. Restlessness & anxiety is probably the most poisonous of the lot, because it makes us distracted, unsettled, and anxious all at the same time. It’s the kind of weed with thorns and sharp-edged leaves. If you run into it, you’re going to end up with a stinging rash all over your body. So if you come across it, destroy it. Don’t let it grow in your field at all.

Breath meditation—keeping the breath steadily in mind—is the best method the Buddha taught for wiping out these hindrances. We use directed thought to focus on the breath, and evaluation to adjust it. Directed thought is like a plow; evaluation, like a harrow. If we keep plowing and harrowing our field, weeds won’t have a chance to grow, and our crops are sure to prosper and bear abundant fruit.

The field here is our body. If we put a lot of thought and evaluation into our breathing, the four properties of the body will be balanced and at peace. The body will be healthy and strong, the mind relaxed and wide open, free from hindrances.

When you’ve got your field cleared and leveled like this, the crops of your mind—the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha—are sure to prosper. As soon as you bring the mind to the breath, you’ll feel a sense of rapture and refreshment. The four bases of success (iddhipāda)—the desire to practice, persistence in the practice, intentness, and circumspection in your practice—will develop step by step. These four qualities are like the four legs of a table that keep it stable and upright. They’re a form of power that supports our strength and our progress to higher levels.

To make another comparison, these four qualities are like the ingredients in a health tonic. Whoever takes this tonic will have a long life. If you want to die, you don’t have to take it, but if you don’t want to die, you have to take a lot. The more you take it, the faster the diseases in your mind will disappear. In other words, your defilements will die. So if you know that your mind has a lot of diseases, this is the tonic for you.

The Art of Letting Go

August 17, 1956

WHEN YOU SIT AND MEDITATE, even if you don’t gain any intuitive insights, make sure at least that you know this much: When the breath comes in, you know. When it goes out, you know. When it’s long, you know. When it’s short, you know. Whether it’s pleasant or unpleasant, you know. If you can know this much, you’re doing fine. As for the various perceptions (saññā) that come into the mind, brush them away—whether they’re good or bad, whether they deal with the past or the future. Don’t let them interfere with what you’re doing—and don’t go chasing after them to straighten them out. When a perception comes passing in, simply let it go passing by on its own. Keep your awareness, unperturbed, in the present.

When we say that the mind goes here or there, it’s not really the mind that goes. Only perceptions go. These perceptions are like shadows of the mind. If the body is still, how will its shadow move? It’s because the body moves and isn’t still that its shadow moves, and when the shadow moves, how will you catch hold of it? Shadows are hard to catch, hard to shake off, hard to set still. The awareness that forms the present: That’s the true mind. The awareness that goes chasing after perceptions is just a shadow. Real awareness—’knowing’—stays in place. It doesn’t stand, walk, come, or go. As for the mind—the awareness that doesn’t act in any way, coming or going, forward or back—it’s quiet and unperturbed. And when the mind is thus its normal, even, undistracted self—i.e., when it doesn’t have any shadows—we can rest peacefully. But if the mind is unstable, uncertain, and wavering, then perceptions arise. When perceptions arise, they go flashing out—and we go chasing after them, hoping to drag them back in. The chasing after them is where we go wrong. So we have to come to a new understanding, that nothing is wrong with the mind. Just watch out for the shadows. You can’t improve your shadow. Say your shadow is black. You can scrub it with soap till your dying day and it’ll still be black—because there’s no substance to it. So it is with perceptions. You can’t straighten them out, because they’re just images, deceiving you.

The Buddha thus taught that whoever isn’t acquainted with the self, the body, the mind, and its shadows, is suffering from avijjā—darkness, deluded knowledge. Whoever thinks the mind is the self, the self is the mind, the mind is its perceptions—whoever has things all mixed up like this—is said to be lost, like a person lost in the jungle. To be lost in the jungle brings all kinds of hardships: the dangers of wild beasts, problems in finding food to eat and a place to sleep. No matter which way you look, there’s no way out. But if we’re lost in the world, it’s many times worse than being lost in the jungle, because we can’t tell night from day. We have no chance to find any brightness because our minds are dark with avijjā.

The purpose of training the mind to be still is to calm down its issues. When its issues are few, the mind can grow quiet. And when the mind is quiet, it’ll gradually become bright, in and of itself, and give rise to knowledge. But if we let things get complicated, knowledge won’t have a chance to arise. That’s darkness.

When intuitive knowledge does arise, it can—if we know how to use it—lead to liberating insight. But if the knowledge concerns lowly matters—dealing with perceptions of the past and future—and we follow it for a long distance, it turns into mundane knowledge. That is to say, we dabble so much in matters of the body and forms (rūpa) that we lower the level of the mind, which doesn’t have a chance to mature in the level of mental phenomena (nāma).

Say, for example, that a vision arises and you get hooked: You gain knowledge of your past lives and get all excited. Things you never knew before, now you can know. Things you never saw before, now you see—and they can make you overly pleased or upset while you follow along with the vision. Why pleased or upset? Because the mind grabs onto them and takes them all too seriously. You may see a vision of yourself prospering as a lord or master, a great emperor or king, wealthy and influential. If you let yourself feel pleased, that’s indulgence in pleasure. You’ve strayed from the Middle Way, which is a mistake. Or you may see yourself as something you wouldn’t care to be: a pig or a dog, a bird or a rat, crippled or deformed. If you let yourself get upset or depressed, that’s indulgence in self-affliction—and again, you’ve strayed from the path and have fallen out of line with the Buddha’s teachings. Some people really let themselves get carried away: As soon as they start seeing things, they begin to think that they’re special, somehow better than other people. They let themselves become proud and conceited—and the right path has disappeared without their even knowing it. This is the way it is with mundane knowledge.

But if you keep one principle firmly in mind, you can stay on the right path: Whatever knowledge appears, whatever the vision—whether good or bad, true or false—you don’t have to feel pleased or upset. Just keep the mind balanced and neutral, and discernment will arise. You’ll see that the vision displays the truth of stress: It arises (is born), fades (ages), and disappears (dies).

If you get hooked on your intuitions, you’re asking for trouble. Latching onto false things can harm you; latching onto true things can harm you. In fact, the true things are what really harm you. If what you know is true and you go telling other people, you’re bragging. If it turns out to be false, it can backfire on you. This is why sages say that knowledge and views are the essence of stress. Why? Because they can harm you. Knowledge is part of the flood of views and opinions (diṭṭhi-ogha) over which we have to cross. If you hang onto knowledge, you’ve gone wrong. If you know, simply know. If you see, simply see, and let it go at that. You don’t have to be excited or pleased. You don’t have to go bragging to other people.

People who’ve studied abroad, when they come back to the rice fields, don’t tell what they’ve learned to the folks at home. They talk about down-home things in a down-home way. They don’t talk about the things they’ve studied because (1) no one would understand them; (2) it wouldn’t serve any purpose. Even with people who would understand them, they don’t display their learning. So it should be when you practice meditation. No matter how much you know, you have to act as if you’re stupid and know nothing—because this is the way people with good manners normally act. If you go bragging to other people, it’s bad enough. If they don’t believe you, it can get even worse.

So whatever you know, simply be aware of it and let it go. Don’t let there be the assumption that ‘I know.’ When you can do this, your mind can attain the transcendent, free from attachment.

Everything in the world has its own truth in every way. Even things that aren’t true are true—i.e., their truth is that they’re false. This is why we have to let go of both what’s true and what’s false. Even then, though, it’s the truth of stress. Once we know the truth and can let it go, we can be at our ease. We won’t be poor, because the truth—the Dhamma—will still be there with us. It’s not a bunch of empty words. It’s like having a lot of money: Instead of lugging it around with us, we keep it piled up at home. We may not have anything in our pockets, but we’re still not poor.

The same is true with people who really know. Even when they let go of their knowledge, it’s still there. This is why the minds of the noble ones aren’t left adrift. They let things go, but not in a wasteful or irresponsible way. They let go like rich people: Even though they let go, they’ve still got piles of wealth.

As for people who let things go like paupers, they don’t know what’s worthwhile and what’s not, and so they throw away all their worthwhile things. When they do this, they’re simply heading for disaster. For instance, they may see that there’s no truth to anything—no truth to the khandhas, no truth to the body, no truth to stress, its cause, its disbanding, or the path to its disbanding, no truth to unbinding (nibbāna). They don’t use their brains at all. They’re too lazy to do anything, so they let go of everything, throw it all away. This is called letting go like a pauper. Like a lot of modern-day ‘sages’: When they come back after they die, they’re going to be poor all over again.

As for the Buddha, he let go only of the true and false things that appeared in his body and mind—but he didn’t abandon his body and mind, which is why he ended up rich and hunger-free, with plenty of wealth to hand down to his descendants. This is why his descendants never have to worry about being poor. Wherever they go, there’s always food filling their bowls. This kind of wealth is more excellent than living atop a palace. Even the wealth of an emperor can’t match it.

So we should look to the Buddha as our model. If we see that the khandhas are no good—inconstant, stressful, not-self, and all that—and simply let go of them by neglecting them, we’re sure to end up poor. Like a stupid person who feels so repulsed by a festering sore on his body that he won’t touch it and so lets it go without taking care of it, letting it keep on stinking and festering: There’s no way the sore is going to heal. As for intelligent people, they know how to wash their sores, put medicine on them, and cover them with bandages so that they’re not disgusting. Eventually, they’re sure to recover.

In the same way, when people who are disgusted with the five khandhas—seeing only their drawbacks and not their good side—and so let them go without putting them to any worthwhile or skillful use, nothing good will come of it. But if we’re intelligent enough to see that the khandhas have their good side as well as their bad, and then put them to good use by meditating to gain discernment into physical and mental phenomena, we’re going to be rich and happy, with plenty to eat even when we just sit around and relax. Poor people are miserable when they have friends, and miserable when they don’t. But once we have the truth—the Dhamma—as our wealth, we won’t suffer if we have money, and won’t suffer if we don’t, because our minds will be transcendent.

As for the various forms of rust that have befouled and obscured our senses—the rust of greed, the rust of anger, and the rust of delusion—these all fall away. Our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind will be all clean and bright. This is why the Buddha said, ‘Dhammo padīpo: The Dhamma is a bright light.’ This is the light of discernment. Our heart will be far beyond all forms of harm and suffering, and will flow in the current leading to nibbāna at all times.

At the Tip of Your Nose

August 26, 1957

WHEN FEELINGS OF PAIN or discomfort arise while you’re sitting in meditation, examine them to see what they come from. Don’t let yourself be pained or upset by them. If there are parts of the body that won’t go as you’d like them to, don’t worry about them. Let them be—because your body is the same as every other body, human or animal, throughout the world: It’s inconstant, stressful, and can’t be forced. So stay with whatever part does go as you’d like it to, and keep it comfortable. This is called dhamma-vicaya: being selective in what’s good.

The body is like a tree: No tree is entirely perfect. At any one time it’ll have new leaves and old leaves, green leaves and yellow, fresh leaves and dry. The dry leaves will fall away first, while those that are fresh will slowly dry out and fall away later. Some of the branches are long, some thick, and some small. The fruits aren’t evenly distributed. The human body isn’t really much different from this. Pleasure and pain aren’t evenly distributed. The parts that ache and those that are comfortable are randomly mixed. You can’t rely on it. So do your best to keep the comfortable parts comfortable. Don’t worry about the parts that you can’t make comfortable.

It’s like going into a house where the floorboards are beginning to rot: If you want to sit down, don’t choose a rotten spot. Choose a spot where the boards are still sound. In other words, the heart needn’t concern itself with things that can’t be controlled.

Or you can compare the body to a mango: If a mango has a rotten or a wormy spot, take a knife and cut it out. Eat just the good part remaining. If you’re foolish enough to eat the wormy part, you’re in for trouble. Your body is the same, and not just the body—the mind, too, doesn’t always go as you’d like it to. Sometimes it’s in a good mood, sometimes it’s not. This is where you have to use as much thought and evaluation as possible.

Directed thought and evaluation are like doing a job. The job here is concentration: centering the mind in stillness. Focus the mind on a single object and then use your mindfulness and alertness to examine and reflect on it. If you use a meager amount of thought and evaluation, your concentration will give meager results. If you do a crude job, you’ll get crude results. If you do a fine job, you’ll get fine results. Crude results aren’t worth much. Fine results are of high quality and are useful in all sorts of ways—like atomic radiation, which is so fine that it can penetrate even mountains. Crude things are of low quality and hard to use. Sometimes you can soak them in water all day long and they still don’t soften up. But as for fine things, all they need is a little dampness in the air and they dissolve.

So it is with the quality of your concentration. If your thinking and evaluation are subtle, thorough, and circumspect, your ‘concentration work’ will result in more and more stillness of mind. If your thinking and evaluation are slipshod and crude, you won’t get much stillness. Your body will ache, and you’ll feel restless and irritable. Once the mind can become very still, though, the body will be comfortable and at ease. Your heart will feel open and clear. Pains will disappear. The elements of the body will feel normal: The warmth in your body will be just right, neither too hot nor too cold. As soon as your work is finished, it’ll result in the highest form of happiness and ease: nibbāna—unbinding. But as long as you still have work to do, your heart won’t get its full measure of peace. Wherever you go, there will always be something nagging at the back of your mind. Once your work is done, though, you can be carefree wherever you go.

If you haven’t finished your job, it’s because (1) you haven’t set your mind on it and (2) you haven’t actually done the work. You’ve shirked your duties and played truant. But if you really set your mind on doing the job, there’s no doubt but that you’ll finish it.

Once you’ve realized that the body is inconstant, stressful, and can’t be forced, you should keep your mind on an even keel with regard to it. ‘Inconstant’ means that it changes. ‘Stressful’ doesn’t refer solely to aches and pains. It refers to pleasure as well—because pleasure is inconstant and undependable, too. A little pleasure can turn into a lot of pleasure, or into pain. Pain can turn back into pleasure, and so on. (If we had nothing but pain we would die.) So we shouldn’t be all that concerned about pleasure and pain. Think of the body as having two parts, like the mango. If you focus your attention on the comfortable part, your mind can be at peace. Let the pains be in the other part. Once you have an object of meditation, you have a comfortable place for your mind to stay. You don’t have to dwell on your pains. You have a comfortable house to live in: Why go sleep in the dirt?

We all want nothing but goodness, but if you can’t tell what’s good from what’s defiled, you can sit and meditate till your dying day and never find nibbāna at all. But if you’re knowledgeable and intent on what you’re doing, it’s not all that hard. Nibbāna is really a simple matter because it’s always there. It never changes. The affairs of the world are what’s hard because they’re always changing and uncertain. Today they’re one way, tomorrow another. Once you’ve done something, you have to keep looking after it. But you don’t have to look after nibbāna at all. Once you’ve realized it, you can let it go. Keep on realizing, keep on letting go—like a person eating rice who, after he’s put the rice in his mouth, keeps spitting it out rather than letting it become feces in his intestines.

What this means is that you keep on doing good but don’t claim it as your own. Do good and then spit it out. This is virāga-dhamma: dispassion. Most people in the world, once they’ve done something, latch onto it as theirs—and so they have to keep looking after it. If they’re not careful, it’ll either get stolen or else wear out on its own. They’re headed for disappointment. Like a person who swallows his rice: After he’s eaten, he’ll have to defecate. After he’s defecated he’ll be hungry again, so he’ll have to eat again and defecate again. The day will never come when he’s had enough. But with nibbāna you don’t have to swallow. You can eat your rice and then spit it out. You can do good and let it go. It’s like plowing a field: The dirt falls off the plow on its own. You don’t need to scoop it up and put it in a bag tied to your water buffalo’s leg. Whoever is stupid enough to scoop up the dirt as it falls off the plow and stick it in a bag will never get anywhere. Either his buffalo will get bogged down, or else he’ll trip over the bag and fall flat on his face right there in the middle of the field. The field will never get plowed, the rice will never get sown, the crop will never get gathered. He’ll have to go hungry.

Buddho, our meditation word, is the name of the Buddha after his awakening. It means someone who has blossomed, who is awake, who has suddenly come to his senses. For six long years before his awakening, the Buddha traveled about, searching for the truth from various teachers, all without success. So he went off on his own and on a full-moon evening in May sat down under the Bodhi tree, vowing not to get up until he had attained the truth. Finally, toward dawn, as he was meditating on his breath, he gained awakening. He found what he was looking for—right at the tip of his nose.

Nibbāna doesn’t lie far away. It’s right at our lips, right at the tip of our nose. But we keep groping around and never find it. If you’re really serious about finding purity, set your mind on meditation and nothing else. As for whatever else may come your way, you can say, ‘No thanks.’ Pleasure? ‘No thanks.’ Pain? ‘No thanks.’ Goodness? ‘No thanks.’ Evil? ‘No thanks.’ Paths and fruitions? ‘No thanks.’ Nibbāna? ‘No thanks.’ If it’s ‘no thanks’ to everything, what will you have left? You won’t need to have anything left. That’s nibbāna. Like a person without any money: How will thieves be able to rob him? If you get money and try to hold onto it, you’re going to get killed. This you want to take. That you want to take. Carry ‘what’s yours’ around till you’re completely weighed down. You’ll never get away.

In this world we have to live with both good and evil. People who have developed dispassion are filled with goodness and know evil fully, but don’t hold onto either, don’t claim either as their own. They put them aside, let them go, and so can travel light and easy. Nibbāna isn’t all that difficult a matter. In the Buddha’s time, some people became arahants while going on their almsround, some while urinating, some while watching farmers plowing a field. What’s difficult about the highest good lies in the beginning, in laying the groundwork—being constantly mindful and alert, examining and evaluating your breath at all times. But if you can keep at it, you’re bound to succeed in the end.

The Care & Feeding of the Mind

May 7, 1959

DIRECTED THOUGHT AND EVALUATION—i.e., adjusting the breath so that it’s comfortable—are like polishing a mirror until it’s clean and bright so that we can see our reflection sharp and clear. When we adjust the breath, we’re adjusting the mind. When we adjust the mind, it’s like dressing the body. And when we dress the body, we’re dressing our reflection. If our body is beautiful, its reflection will have to be beautiful, too.

Or you could say that it’s like looking into different types of mirrors, which will transform our reflection in different ways. Say you look into a convex mirror: Your reflection will be taller than you are. If you look in a concave mirror, your reflection will be abnormally short. But if you look into a mirror that’s flat, smooth, and normal, it’ll give you a true reflection of yourself.

In the same way, adjusting the breath to put it in good order is tantamount to putting the mind in good order as well, and can give all kinds of benefits—like an intelligent cook who knows how to prepare food so that its taste is new and nourishing in a way that appeals to her employer. Sometime she changes the color, sometimes the flavor, sometimes the shape. She doesn’t simply keep fixing things the way she always has, all year round or all her life—i.e., porridge today, porridge tomorrow, porridge the next day, to the point where her employer has to go looking for a new cook. An intelligent cook who knows how to vary her offerings so that her employer is always satisfied and doesn’t grow tired of her cooking is sure to get a raise in her salary, or maybe a special bonus.

In the same way, if you know how to adjust and vary the breath—if you’re always thinking about and evaluating the various breaths in the body—you’ll become thoroughly mindful and expert in all matters dealing with the breath and the other properties of the body. You’ll always know how things are going with the body. Rapture, ease, and singleness will come on their own. The body will be full; the mind will be full; the body at ease and the mind at peace. All the properties will be at peace, free from unrest and disturbances.

It’s like knowing how to look after a small child. If your child starts crying, you know when to give it milk or candy, when to give it a bath, when to take it out for some air, when to rock it in a cradle, when to give it a toy or a doll to play with. The child will stop crying, stop whining, and leave you free to finish whatever your work. The mind is like a small, innocent child. If you’re skilled at looking after it, it’ll be obedient, happy, and contented, and will grow day by day.

When the body and mind are full and content, they won’t feel hungry. They won’t have to go opening up the pots and pans on the stove or pace around looking out the windows and doors. They can sleep in peace without any disturbances. Ghosts and demons—the pains of the khandhas—won’t come and possess them. This way we can be at our ease, because when we sit, we sit with people. When we lie down, we lie down with people. When we eat, we eat with people. When people live with people, there’s no problem; but when they live with ghosts and demons, they’re sure to squabble and never find any peace. If we don’t know how to evaluate and adjust our breathing, there’s no way our practice of concentration will give any results. Even if we sit till we die, we won’t gain any knowledge or understanding at all.

There was once an old monk—70 years old, 30 years in the monkhood—who had heard good things about how I teach meditation and so came to study with me. The first thing he asked was, ‘What method do you teach?’

‘Breath meditation,’ I told him. ‘You know—bud-dho, bud-dho.’

As soon as he heard that, he said, ‘I’ve been practicing that method ever since the time of Ajaan Mun—buddho, buddho ever since I was young—and I’ve never seen anything good come of it. All it does is buddho, buddho without ever getting anywhere at all. And now you’re going to teach me to buddho some more. What for? You want me to buddho till I die?’

This is what happens when people have no sense of how to adjust and evaluate their breathing: They’ll never find what they’re looking for—which is why adjusting and spreading the breath is a very important part of doing breath meditation.

Getting to know yourself—becoming acquainted with your body, your mind, the properties of earth, water, fire, wind, space, and consciousness, knowing what they come from, how they arise, how they disband, how they’re inconstant, stressful, and not-self: All of this you have to find out by trying to explore on your own. Only then will your knowledge be of real use. If your knowledge simply follows what’s in books or what other people tell you, it’s knowledge that comes from labels and concepts, not from your own discernment. It’s not really knowledge. Knowing only what other people tell you is like following them down a road—and what could be good about that? They might lead you down the wrong road. And if the road is dusty, they might kick dust into your ears and eyes.… So in your practice of the Dhamma, don’t simply believe what other people say. Don’t believe labels. Practice concentration until you gain knowledge on your own. Only then will it count as discernment. Only then will it be safe.

‘Just Right’ Concentration

October 4, 1960

WHEN YOU MEDITATE, you have to think. If you don’t think, you can’t meditate, because thinking forms a necessary part of meditation. Take jhāna, for instance. Use your powers of directed thought to bring the mind to the object, and your powers of evaluation to be discriminating in your choice of an object. Examine the object of your meditation until you see that it’s just right for you. You can choose slow breathing, fast breathing, short breathing, long breathing, narrow breathing, broad breathing; hot, cool, or warm breathing; a breath that goes only as far as the nose, a breath that goes only as far as the base of the throat, a breath that goes all the way down to the heart. When you’ve found an object that suits your taste, catch hold of it and make the mind one, focused on a single object. Once you’ve done this, evaluate your object. Direct your thoughts to making it stand out. Don’t let the mind leave the object. Don’t let the object leave the mind. Tell yourself that it’s like eating: Put the food in line with your mouth, put your mouth in line with the food. Don’t miss. If you miss and go sticking the food in your ear, under your chin, in your eye, or on your forehead, you’ll never get anywhere in your eating.

So it is with your meditation. Sometimes the ‘one’ object of your mind takes a sudden sharp turn into the past, back hundreds of years. Sometimes it takes off into the future and comes back with all sorts of things to clutter your mind. This is like taking your food, sticking it up over your head, and letting it fall down behind you—the dogs are sure to get it; or like bringing the food to your mouth and then tossing it out in front of you. When you find this happening, it’s a sign that your mind hasn’t been made snug with its object. Your powers of directed thought aren’t firm enough. You have to bring the mind to the object and then keep after it to make sure it stays put. Like eating: Make sure the food is in line with the mouth and stick it right in. This is directed thought: The food is in line with the mouth, the mouth is in line with the food. You’re sure it’s food and you know what kind it is—main course or dessert, coarse or refined.

Once you know what’s what, and it’s in your mouth, chew it right up. This is evaluation: examining, reviewing your meditation. Sometimes this comes under threshold concentration—examining a coarse object to make it more and more refined. If you find that the breath is long, examine long breathing. If it’s short, examine short breathing. If it’s slow, examine slow breathing—to see if the mind will stay with that kind of breathing, to see if that kind of breathing will stay with the mind, to see whether the breath is smooth and unhindered. This is evaluation.

When the mind gives rise to directed thought and evaluation, you have both concentration and discernment. Directed thought and singleness of preoccupation fall under the heading of concentration; evaluation, under the heading of discernment. When you have both concentration and discernment, the mind is still and knowledge can arise. But if there’s too much evaluation, it can destroy your stillness of mind. If there’s too much stillness, it can snuff out thought. You have to watch over the stillness of your mind to make sure you have things in the right proportions. If you don’t have a sense of ‘just right,’ you’re in for trouble. If the mind is too still, your progress will be slow. If you think too much, it’ll run away with your concentration.

So observe things carefully. Again, it’s like eating. If you go shoveling food into your mouth, you might end up choking to death. You have to ask yourself: Is it good for me? Can I handle it? Are my teeth strong enough? Some people have nothing but empty gums and yet they want to eat sugar cane: It’s not normal. Some people, even though their teeth are aching and falling out, still want to eat crunchy foods. So it is with the mind: As soon as it’s just a little bit still, we want to see this, know that—we want to take on more than we can handle. You first have to make sure that your concentration is solidly based, that your discernment and concentration are properly balanced. This point is very important. Your powers of evaluation have to be ripe, your directed thought firm.

Say you have a water buffalo, tie it to a stake, and pound the stake deep into the ground. If your buffalo is strong, it just might walk or run away with the stake. You have to know your buffalo’s strength. If it’s really strong, pound the stake so that it’s firmly in the ground and keep watch over it. In other words, if you find that the obsessiveness of your thinking is getting out of hand, going beyond the bounds of mental stillness, then fix the mind in place and make it extra still—but not so still that you lose track of things. If the mind is too quiet, it’s like being in a daze. You don’t know what’s going on at all. Everything is dark, blotted out. Or else you have good and bad spells, sinking out of sight and then popping up again. This is concentration without directed thought or evaluation, with no sense of judgment: Wrong Concentration.

So you have to be observant. Use your judgment—but don’t let the mind get carried away by its thoughts. Your thinking is something separate. The mind stays with the meditation object. Wherever your thoughts may go spinning, your mind is still firmly based—like holding onto a post and spinning around and around. You can keep on spinning, and yet it doesn’t wear you out. But if you let go of the post and spin around three times, you get dizzy and—Bang!—fall flat on your face. So it is with the mind: If it stays with the singleness of its preoccupation, it can keep thinking and not get tired, not get harmed, because your thinking and stillness are right there together. The more you think, the more solid your mind gets. The more you sit and meditate, the more you think. The mind becomes more and more firm until all the hindrances (nīvaraṇa) fall away. The mind no longer goes looking for concepts. Now it can give rise to knowledge.

The knowledge here isn’t ordinary knowledge. It washes away your old knowledge. You don’t want the knowledge that comes from ordinary thinking and reasoning: Let go of it. You don’t want the knowledge that comes from directed thought and evaluation: Stop. Make the mind quiet. Still. When the mind is still and unhindered, this is the essence of all that’s skillful and good. When your mind is on this level, it isn’t attached to any concepts at all. All the concepts you’ve known—dealing with the world or the Dhamma, however many or few—are washed away. Only when they’re washed away can new knowledge arise.

This is why you should let go of concepts—all the labels and names you have for things. You have to let yourself be poor. It’s when people are poor that they become ingenious and resourceful. If you don’t let yourself be poor, you’ll never gain discernment. In other words, you don’t have to be afraid of being stupid or of missing out on things. You don’t have to be afraid that you’ve hit a dead end. You don’t want any of the insights you’ve gained from listening to others or from reading books, because they’re concepts and therefore inconstant. You don’t want any of the insights you’ve gained by reasoning and thinking, because they’re concepts and therefore not-self. Let all these insights disappear, leaving just the mind, firmly intent, leaning neither to the left, toward being displeased; nor to the right, toward being pleased. Keep the mind still, quiet, neutral, impassive—set tall. And there you are: right concentration.

When right concentration arises in the mind, it has a shadow. When you can catch sight of the shadow appearing, that’s vipassanā: liberating insight.

The knowledge you gain from right concentration doesn’t come in the form of thoughts or ideas. It comes as right views. What looks wrong to you is really wrong. What looks right is really right. If what looks right is really wrong, that’s wrong view. If what looks wrong is really right, again—wrong view. With right view, though, right looks right and wrong looks wrong.

To put it in terms of cause and effect, you see the four noble truths. You see stress, and it really is stressful. You see the cause of stress arising, and that it’s really causing stress. These are noble truths: absolutely, undeniably, indisputably true. You see that stress has a cause. Once the cause arises, there has to be stress. As for the way to the disbanding of stress, you see that the path you’re following will, without a doubt, lead to unbinding. Whether or not you go all the way, what you see is correct. This is right view. And as for the disbanding of stress, you see that there really is such a thing. You see that as long as you’re on the path, stress does in fact fall away. When you come to realize the truth of these things in your heart, that’s vipassanā-ñāṇa.

To put it even more simply: You see that all things, inside as well as out, are undependable. The body is undependable, aging is undependable, death is undependable. They’re slippery characters, constantly changing on you. To see this is to see inconstancy. Don’t let yourself be pleased by inconstancy. Don’t let yourself be upset. Keep the mind neutral, on an even keel. That’s what’s meant by vipassanā.

As for stress: Say we hear that an enemy is suffering. ‘Glad to hear it,’ we think. ‘Hope they hurry up and die.’ The heart has tilted. Say we hear that a friend has become wealthy, and we become happy; or a son or daughter is ill, and we become sad. Our mind has fallen in with suffering and stress. Why? Because we’re unskilled. The mind isn’t centered—i.e., it’s not in right concentration. We have to look after the mind. Don’t let it fall in with stress. Whatever suffers, let it suffer, but don’t let the mind suffer with it. The body may be in pain, but the mind isn’t pained. Let the body go ahead and suffer, but the mind doesn’t suffer. Keep the mind neutral. Don’t be pleased by pleasure—pleasure is a form of stress, you know. How so? It can change. It can rise and fall. It can be high and low. It can’t last. That’s stress. Pain is also stress: double stress. When you gain this sort of insight into stress—when you really see stress—vipassanā has arisen in the mind.

As for anattā, not-self: Once we’ve examined things and seen them for what they really are, we don’t make claims, we don’t display influence, we don’t try to show that we have the right or the power to bring things that are not-self under our control. No matter how hard we try, we can’t prevent birth, aging, illness, and death. If the body is going to be old, let it be old. If it’s going to hurt, let it hurt. If it has to die, let it die. Don’t be pleased by death, either your own or that of others. Don’t be upset by death, your own or that of others. Keep the mind neutral. Unruffled. Unfazed. This is saṅkhārūpekkhā-ñāṇa: letting saṅkhāras—all things fashioned and fabricated—follow their own inherent nature.

This, briefly, is vipassanā: You see that all fabrications are inconstant, stressful, and not-self. You can disentangle them from your grasp. You can let go. This is where it gets good. How so? You don’t have to wear yourself out, lugging saṅkhāras around.

To be attached means to carry a load, and there are five heaps (khandhas) we carry: attachment to physical phenomena, to feelings, to concepts and labels, to mental fabrications, and to sensory consciousness. We grab hold and hang onto these things, thinking that they’re the self. Go ahead: Carry them around. Hang one load from your left leg and one from your right. Put one on your left shoulder and one on your right. Put the last load on your head. And now: Carry them wherever you go—clumsy, encumbered, and comical.

bhārā have pañcakkhandhā

Go ahead and carry them.

The five khandhas are a heavy load,

bhārahāro ca puggalo

and as individuals we burden ourselves with them.

bhārādānaṁ dukkhaṁ loke

Carry them everywhere you go, and you waste your time

suffering in the world.

The Buddha taught that whoever lacks discernment, whoever is unskilled, whoever doesn’t practice concentration leading to liberating insight, will have to be burdened with stress, will always be loaded down. It’s a pity. It’s a shame. They’ll never get away. Their legs are burdened, their shoulders burdened—and where are they going? Three steps forward and two steps back. Soon they’ll get discouraged and then, after a while, they’ll pick themselves up and get going again.

Now, when we see inconstancy—that all fabrications, whether within us or without, are undependable; when we see that they’re stressful; when we see that they’re not our self, that they simply whirl around in and of themselves: When we gain these insights, we can put down our burdens, i.e., let go of our attachments. We can put down the past—i.e., stop dwelling in it. We can let go of the future—i.e., stop yearning for it. We can let go of the present—i.e., stop claiming it as the self. Once these three big baskets have fallen from our shoulders, we can walk with a light step. We can even dance. We’re beautiful. Wherever we go, people will be glad to know us. Why? Because we’re not encumbered. Whatever we do, we can do with ease. We can walk, run, dance, and sing—all with a light heart. We’re Buddhism’s beauty, a sight for sore eyes, graceful wherever we go. No longer burdened, no longer encumbered, we can be at our ease. This is vipassanā-ñāṇa.