Keeping The Breath In Mind

Keeping the Breath in Mind

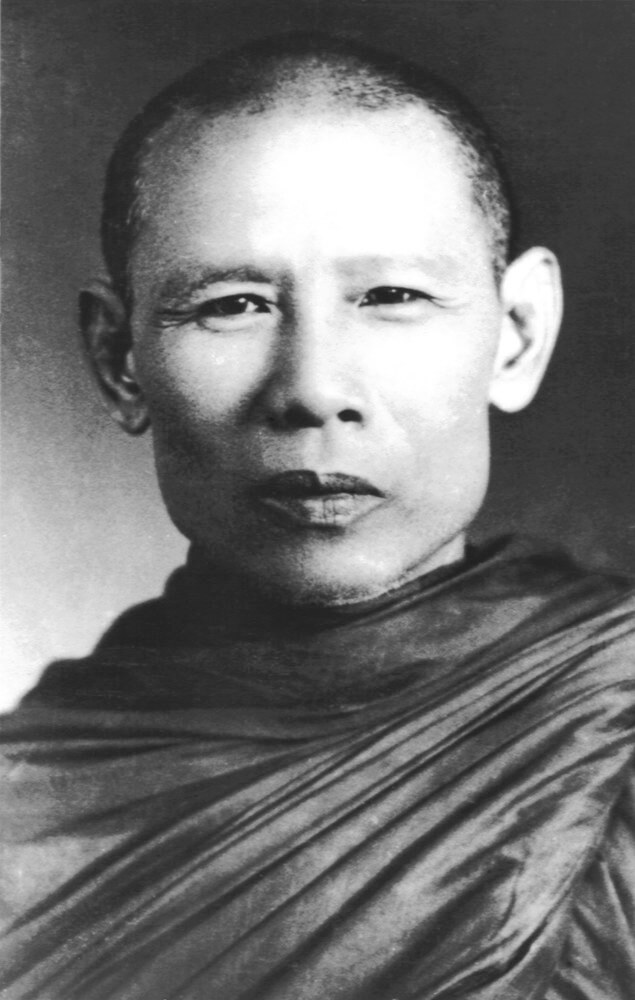

Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo

Introduction

THIS BOOK is a guide to the practice of centering the mind. There are two sections: The first deals almost exclusively with the mind. But because the well-being of the mind depends to some extent on the body, I have included a second section [Method 2] that shows how to use the body to benefit the mind.

From what I’ve observed in my own practice, there is only one path that is short, easy, effective, and pleasant, and at the same time has hardly anything to lead you astray: the path of keeping the breath in mind, the same path the Lord Buddha himself used with such good results. I hope that you won’t make things difficult for yourself by being hesitant or uncertain, by taking this or that teaching from here or there; and that, instead, you’ll earnestly set your mind on getting in touch with your own breath and following it as far as it can take you. From there, you will enter the stage of liberating insight, leading to the mind itself. Ultimately, pure knowing—buddha—will stand out on its own. That’s when you’ll reach an attainment trustworthy and sure. In other words, if you let the breath follow its own nature, and the mind its own nature, the results of your practice will without a doubt be all that you hope for.

Ordinarily, the nature of the heart, if it isn’t trained and put into order, is to fall in with preoccupations that are stressful and bad. This is why we have to search for a principle—a Dhamma—with which to train ourselves if we hope for happiness that’s stable and secure. If our hearts have no inner principle, no center in which to dwell, we’re like a person without a home. Homeless people have nothing but hardship. The sun, wind, rain, and dirt are bound to leave them constantly soiled because they have nothing to act as shelter. To practice centering the mind is to build a home for yourself: Momentary concentration (khaṇika samādhi) is like a house roofed with thatch; threshold concentration (upācāra samādhi), a house roofed with tile; and fixed penetration (appanā samādhi), a house built out of brick. Once you have a home, you’ll have a safe place to keep your valuables. You won’t have to put up with the hardships of watching over them, the way a person who has no place to keep his valuables has to go sleeping in the open, exposed to the sun and rain, to guard those valuables—and even then his valuables aren’t really safe.

So it is with the uncentered mind: It goes searching for good from other areas, letting its thoughts wander around in all kinds of concepts and preoccupations. Even if those thoughts are good, we still can’t say that we’re safe. We’re like a woman with plenty of jewelry: If she dresses up in her jewels and goes wandering around, she’s not safe at all. Her wealth might even lead to her own death. In the same way, if our hearts aren’t trained through meditation to gain inner stillness, even the virtues we’ve been able to develop will deteriorate easily because they aren’t yet securely stashed away in the heart. To train the mind to attain stillness and peace, though, is like keeping your valuables in a strongbox.

This is why most of us don’t get any good from the good we do. We let the mind fall under the sway of its various preoccupations. These preoccupations are our enemies, because there are times when they can cause the virtues we’ve already developed to wither away. The mind is like a blooming flower: If wind and insects disturb the flower, it may never have a chance to give fruit. The flower here stands for the stillness of the mind on the path; the fruit, for the happiness of the path’s fruition. If our stillness of mind and happiness are constant, we have a chance to attain the ultimate good we all hope for.

The ultimate good is like the heartwood of a tree. Other ‘goods’ are like the buds, branches, and leaves. If we haven’t trained our hearts and minds, we’ll meet with things that are good only on the external level. But if our hearts are pure and good within, everything external will follow in becoming good as a result. Just as our hand, if it’s clean, won’t soil what it touches, but if it’s dirty, will spoil even the cleanest cloth; in the same way, if the heart is defiled, everything is defiled. Even the good we do will be defiled, for the highest power in the world—the sole power giving rise to all good and evil, pleasure and pain—is the heart. The heart is like a god. Good, evil, pleasure, and pain come entirely from the heart. We could even call the heart a creator of the world, because the peace and continued well-being of the world depend on the heart. If the world is to be destroyed, it will be because of the heart. So we should train this most important part of the world to be centered as a foundation for its wealth and well-being.

Centering the mind is a way of gathering together all its skillful potentials. When these potentials are gathered in the right proportions, they’ll give you the strength you need to destroy your enemies: all your defilements and unwise mental states. You have discernment that you’ve trained and made wise in the ways of good and evil, of the world and the Dhamma. Your discernment is like gunpowder. But if you keep your gunpowder for long without putting it into bullets—a centered mind—it’ll go damp and moldy. Or if you’re careless and let the fires of greed, anger, or delusion overcome you, your gunpowder may flame up in your hands. So don’t delay. Put your gunpowder into bullets so that whenever your enemies—your defilements—make an attack, you’ll be able to shoot them right down.

Whoever trains the mind to be centered gains a refuge. A centered mind is like a fortress. Discernment is like a weapon. To practice centering the mind is to secure yourself in a fortress, and so is something very worthwhile and important.

Virtue, the first part of the path, and discernment, the last, aren’t especially difficult. But keeping the mind centered, which is the middle part, takes some effort because it’s a matter of forcing the mind into shape. Admittedly, centering the mind, like placing bridge pilings in the middle of a river, is something difficult to do. But once the mind is firmly in place, it can be very useful in developing virtue and discernment. Virtue is like placing pilings on the near shore of the river; discernment, like placing them on the far shore. But if the middle pilings—a centered mind—aren’t firmly in place, how will you ever be able to bridge the flood of suffering?

There is only one way we can properly reach the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha, and that’s through the practice of mental development (bhāvanā). When we develop the mind to be centered and still, discernment can arise. Discernment here refers not to ordinary discernment, but to the insight that comes solely from dealing directly with the mind. For example, the ability to remember past lives, to know where living beings are reborn after death, and to cleanse the heart of the fermentations (āsava) of defilement: These three forms of intuition—termed ñāṇa-cakkhu, the eye of the mind—can arise for people who train themselves in the area of the heart and mind. But if we go around searching for knowledge from sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations mixed together with concepts, it’s as if we were studying with the Six Masters, and so we can’t clearly see the truth—just as the Buddha, while he was studying with the Six Masters, wasn’t able to gain awakening. He then turned his attention to his own heart and mind, and went off to practice on his own, keeping track of his breath as his first step and going all the way to the ultimate goal. As long as you’re still searching for knowledge from your six senses, you’re studying with the Six Masters. But when you focus your attention on the breath—which exists in each of us—to the point where the mind settles down and is centered, you’ll have the chance to meet with the real thing: buddha, pure knowing.

Some people believe that they don’t have to practice centering the mind, that they can attain release through discernment (paññā-vimutti) by working at discernment alone. This simply isn’t true. Both release through discernment and release through stillness of mind (ceto-vimutti) are based on centering the mind. They differ only in degree. Like walking: Ordinarily, a person doesn’t walk on one leg alone. Whichever leg is heavier is simply a matter of personal habits and traits.

Release through discernment begins by pondering various events and aspects of the world until the mind slowly comes to rest and, once it’s still, gives rise intuitively to liberating insight (vipassanā-ñāṇa): clear and true understanding in terms of the four noble truths (ariya-sacca). In release through stillness of mind, though, there’s not much pondering involved. The mind is simply forced to be quiet until it attains the stage of fixed penetration. That’s where intuitive insight will arise, enabling it to see things for what they are. This is release through stillness of mind: Concentration comes first, discernment later.

A person with a wide-ranging knowledge of the texts—well-versed in their letter and meaning, capable of clearly and correctly explaining various points of doctrine—but with no inner center for the mind, is like a pilot flying about in an airplane with a clear view of the clouds and stars but no sense of where the landing strip is. He’s headed for trouble. If he flies higher, he’ll run out of air. All he can do is keep flying around until he runs out of fuel and comes crashing down in the savage wilds.

Some people, even though they are highly educated, are no better than savages in their behavior. This is because they’ve gotten carried away, up in the clouds. Some people—taken with what they feel to be the high level of their own learning, ideas, and opinions—won’t practice centering the mind because they feel it beneath them. They think they deserve to go straight to release through discernment instead. Actually, they’re heading straight to disaster, like the airplane pilot who has lost sight of the landing strip.

To practice centering the mind is to build a landing strip for yourself. Then, when discernment comes, you’ll be able to attain release safely.

This is why we have to develop all three parts of the path—virtue, concentration, and discernment—if we want to be complete in our practice of the religion. Otherwise, how can we say that we know the four noble truths?—because the path, to qualify as the noble path, has to be composed of virtue, concentration, and discernment. If we don’t develop it within ourselves, we can’t know it. And if we don’t know, how can we let go?

Most of us, by and large, like getting results but don’t like laying the groundwork. We may want nothing but goodness and purity, but if we haven’t completed the groundwork, we’ll have to keep on being poor. Like people who are fond of money but not of work: How can they be good, solid citizens? When they feel the pinch of poverty, they’ll turn to corruption and crime. In the same way, if we aim at results in the field of the religion but don’t like doing the work, we’ll have to continue being poor. And as long as our hearts are poor, we’re bound to go searching for goodness in other areas—greed, gain, status, pleasure, and praise, the baits of the world—even though we know better. This is because we don’t truly know, which means simply that we aren’t true in what we do.

The truth of the path is always true. Virtue is something true, concentration is true, discernment is true, release is true. But if we aren’t true, we won’t meet with anything true. If we aren’t true in practicing virtue, concentration, and discernment, we’ll end up only with things that are fake and imitation. And when we make use of things fake and imitation, we’re headed for trouble. So we have to be true in our hearts. When our hearts are true, we’ll come to savor the taste of the Dhamma, a taste surpassing all the tastes of the world.

This is why I have put together the following two guides for keeping the breath in mind.

Peace.

Phra Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo

WAT BOROMNIVAS

BANGKOK, 1953

Preliminaries

NOW I WILL EXPLAIN how to go about the practice of centering the mind. Before starting out, kneel down with your hands palm-to-palm in front of your heart and sincerely pay respect to the Triple Gem, saying as follows:

Arahaṁ sammā-sambuddho bhagavā:

Buddhaṁ bhagavantaṁ abhivādemi. (bow down)

Svākkhāto bhagavatā dhammo:

Dhammaṁ namassāmi. (bow down)

Supaṭipanno bhagavato sāvaka-saṅgho:

Saṅghaṁ namāmi. (bow down)

Then, showing respect with your thoughts, words, and deeds, pay homage to the Buddha:

Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammā-sambuddhasa. (three times)

And take refuge in the Triple Gem:

Buddhaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Dhammaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Saṅghaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Dutiyampi buddhaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Dutiyampi dhammaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Dutiyampi saṅghaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Tatiyampi buddhaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Tatiyampi dhammaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Tatiyampi saṅghaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Then make the following resolution: ‘I take refuge in the Buddha—the Pure One, completely free from defilement; and in his Dhamma—doctrine, practice, and attainment; and in the Sangha—the four levels of his noble disciples—from now to the end of my life.’

Buddhaṁ jīvitaṁ yāva nibbānaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Dhammaṁ jīvitaṁ yāva nibbānaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Saṅghaṁ jīvitaṁ yāva nibbānaṁ saraṇaṁ gacchāmi.

Then formulate the intention to observe the five, eight, ten, or 227 precepts according to how many you are normally able to observe, expressing them in a single vow:

Imāni pañca sikkhāpadāni samādiyāmi. (three times)

(This is for the observing the five precepts, and means, ‘I undertake the five training rules: to refrain from taking life, from stealing, from sexual misconduct, from lying, and from taking intoxicants.’)

Imāni aṭṭha sikkhāpadāni samādiyāmi. (three times)

(This is for those observing the eight precepts, and means, ‘I undertake the eight training rules: to refrain from taking life, from stealing, from sexual intercourse, from lying, from taking intoxicants, from eating food after noon and before dawn, from watching shows and from adorning the body for the purpose of beautifying it, and from using high and luxurious beds and seats.’)

Imāni dasa sikkhāpadāni samādiyāmi. (three times)

(This is for those observing the ten precepts, and means, ‘I undertake the ten training rules: to refrain from taking life, from stealing, from sexual intercourse, from lying, from taking intoxicants, from eating food after noon and before dawn, from watching shows, from adorning the body for the purpose of beautifying it, from using high and luxurious beds and seats, and from receiving money.’)

Parisuddho ahaṁ bhante. Parisuddhoti maṁ buddho dhammo saṅgho dhāretu.

(This is for those observing the 227 precepts.)

Now that you have professed the purity of your thoughts, words, and deeds toward the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha, bow down three times. Sit down, place your hands palm-to-palm in front of your heart, steady your thoughts, and develop the four sublime attitudes: goodwill, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity. To spread these thoughts to all living beings without exception is called the immeasurable Sublime Attitude. A short Pali formula for those who have trouble memorizing is:

“Mettā” (goodwill and benevolence, hoping for your own welfare and that of all other living beings.)

“Karuṇā” (compassion for yourself and others.)

“Muditā” (empathetic joy, taking delight in your own goodness and that of others.)

“Upekkhā” (equanimity in the face of things that should be let be.)

Method 1

SIT IN A HALF-LOTUS POSITION, right leg on top of the left leg, your hands placed palm-up on your lap, right hand on top of the left. Keep your body straight and your mind on the task before you. Raise your hands in respect, palm-to-palm in front of the heart, and think of the qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha: Buddho me nātho—The Buddha is my mainstay. Dhammo me nātho—The Dhamma is my mainstay. Saṅgho me nātho—The Sangha is my mainstay. Then repeat in your mind, buddho, buddho; dhammo, dhammo; saṅgho, saṅgho. Return your hands to your lap and repeat one word, buddho, three times in your mind.

Then think of the in-and-out breath, counting the breaths in pairs. First think bud- with the in-breath, dho with the out, ten times. Then begin again, thinking buddho with the in-breath, buddho with the out, seven times. Then begin again: As the breath goes in and out once, think buddho once, five times. Then begin again: As the breath goes in and out once, think buddho three times. Do this for three in-and-out breaths.

Now you can stop counting the breaths, and simply think bud- with the in-breath and dho with the out. Let the breath be relaxed and natural. Keep your mind perfectly still, focused on the breath as it comes in and out of the nostrils. When the breath goes out, don’t send the mind out after it. When the breath comes in, don’t let the mind follow it in. Let your awareness be broad, cheerful, and open. Don’t force the mind too much. Relax. Pretend that you’re breathing out in the wide open air. Keep the mind still, like a post at the edge of the sea. When the water rises, the post doesn’t rise with it; when the water ebbs, the post doesn’t sink.

When you’ve reached this level of stillness, you can stop thinking buddho. Simply be aware of the feeling of the breath.

Then slowly bring your attention inward, focusing it on the various aspects of the breath—the important aspects that can give rise to intuitive powers of various kinds: clairvoyance, clairaudience, the ability to know the minds of others, the ability to remember previous lives, the ability to know where different people and animals are reborn after death, and knowledge of the various elements or potentials that are connected with, and can be of use to, the body. These elements come from the bases of the breath. The First Base: Center the mind on the tip of the nose and then slowly move it to the middle of the forehead, the Second Base. Keep your awareness broad. Let the mind rest for a moment at the forehead and then bring it back to the nose. Keep moving it back and forth between the nose and the forehead—like a person climbing up and down a mountain—seven times. Then let it settle at the forehead. Don’t let it go back to the nose.

From here, let it move to the Third Base, the middle of the top of the head, and let it settle there for a moment. Keep your awareness broad. Inhale the breath at that spot, let it spread throughout the head for a moment, and then return the mind to the middle of the forehead. Move the mind back and forth between the forehead and the top of the head seven times, finally letting it rest on the top of the head.

Then bring it into the Fourth Base, the middle of the brain. Let it be still for a moment and then bring it back out to the top of the head. Keep moving it back and forth between these two spots, finally letting it settle in the middle of the brain. Keep your awareness broad. Let the refined breath in the brain spread to the lower parts of the body.

When you reach this point you may find that the breath starts giving rise to various signs (nimitta), such as seeing or feeling hot, cold, or tingling sensations in the head. You may see a pale, murky vapor or your own skull. Even so, don’t let yourself be affected by whatever appears. If you don’t want the nimitta to appear, breathe deep and long, down into the heart, and it will immediately go away.

When you see that a nimitta has appeared, mindfully focus your awareness on it—but be sure to focus on only one at a time, choosing whichever one is most comfortable. Once you’ve got hold of it, expand it so that it’s as large as your head. The bright white nimitta is useful to the body and mind: It’s a pure breath that can cleanse the blood in the body, reducing or eliminating feelings of physical pain.

When you have this white light as large as the head, bring it down to The Fifth Base, the center of the chest. Once it’s firmly settled, let it spread out to fill the chest. Make this breath as white and as bright as possible, and then let both the breath and the light spread throughout the body, out to every pore, until different parts of the body appear on their own as pictures. If you don’t want the pictures, take two or three long breaths and they’ll disappear. Keep your awareness still and expansive. Don’t let it latch onto or be affected by any nimitta that may happen to pass into the brightness of the breath. Keep careful watch over the mind. Keep it one. Keep it intent on a single preoccupation, the refined breath, letting this refined breath suffuse the entire body.

When you’ve reached this point, knowledge will gradually begin to unfold. The body will be light, like fluff. The mind will be rested and refreshed—supple, solitary, and self-contained. There will be an extreme sense of physical pleasure and mental ease.

If you want to acquire knowledge and skill, practice these steps until you’re adept at entering, leaving, and staying in place. When you’ve mastered them, you’ll be able to give rise to the nimitta of the breath—the brilliantly white ball or lump of light—whenever you want. When you want knowledge, simply make the mind still and let go of all preoccupations, leaving just the brightness and emptiness. Think one or two times of whatever you want to know—of things inside or outside, concerning yourself or others—and the knowledge will arise or a mental picture will appear. To become thoroughly expert you should, if possible, study directly with someone who has practiced and is skilled in these matters, because knowledge of this sort can come only from the practice of centering the mind.

The knowledge that comes from centering the mind falls into two classes: mundane (lokiya) and transcendent (lokuttara). With mundane knowledge, you’re attached to your knowledge and views on the one hand, and to the things that appear and give rise to your knowledge on the other. Your knowledge and the things that give you knowledge through the power of your skill are composed of true and false mixed together—but the ‘true’ here is true simply on the level of mental fabrication, and anything fabricated is by nature changeable, unstable, and inconstant.

So when you want to go on to the transcendent level, gather all the things you know and see into a single preoccupation—ekaggatārammaṇa, the singleness of mental absorption—and see that they are all of the same nature. Take all your knowledge and awareness and gather it into the same point, until you can clearly see the truth: that all of these things, by their nature, simply arise and pass away. Don’t try to latch onto the things you know—your preoccupations—as yours. Don’t try to latch onto the knowledge that has come from within you as your own. Let these things be, in line with their own inherent nature. If you latch onto your pre-occupations, you’re latching onto stress and pain. If you hold onto your knowledge, it will turn into the cause of stress.

So: A mind centered and still gives rise to knowledge. This knowledge is the path. All of the things that come passing by for you to know are stress. Don’t let the mind fasten onto its knowledge. Don’t let it fasten onto the preoccupations that appear for you to know. Let them be, in line with their nature. Put your mind at ease. Don’t fasten onto the mind or suppose it to be this or that. As long as you suppose yourself, you’re suffering from obscured awareness (avijjā). When you can truly know this, the transcendent will arise within you—the noblest good, the most exalted happiness a human being can know.

To summarize, the basic steps to practice are as follows:

1. Eliminate all bad preoccupations from the mind.

2. Make the mind dwell on good preoccupations.

3. Gather all good preoccupations into one—the singleness of meditative absorption (jhāna).

4. Consider this one preoccupation until you see how it is aniccaṁ, inconstant; dukkhaṁ, stressful; and anattā, not yourself or anyone else—empty and void.

5. Let all good and bad preoccupations follow their own nature—because good and bad dwell together and are equal by nature. Let the mind follow its own nature. Let knowing follow its own nature. Knowing doesn’t arise, and it doesn’t fall away. This is santi-dhamma—the reality of peace. It knows goodness, but the knowing isn’t goodness, and goodness isn’t the knowing. It knows evil, but the knowing isn’t evil, and evil isn’t the knowing. In other words, knowing isn’t attached to knowledge or to the things known. Its nature is truly elemental—flawless and pure, like a drop of water on a lotus leaf. This is why it’s called asaṅkhata-dhātu: the unfabricated property, a true element.

When you can follow these five steps, you’ll find marvels appearing in your heart, the skills and perfections that come from having practiced tranquility and insight meditation. You’ll obtain the two types of results already mentioned:

mundane, providing for your own physical well-being and that of others throughout the world; and

transcendent, providing for the well-being of your heart, bringing happiness that is calm, cool, and blooming, leading all the way to unbinding (nibbāna)—free from birth, aging, illness, and death.

This has been a brief explanation of the main principles of breath meditation. If you have any questions or encounter any difficulties in putting these principles into practice, and you wish to study directly with someone who teaches along these lines, I will be happy to help you to the best of my ability so that we can all attain the peace and well-being taught by the religion.

Most people will find that Method 2, which follows, is easier and more relaxing than Method 1, outlined above.